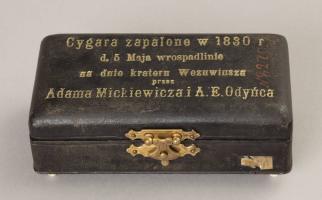

Exhibit of the Month is a series initiated by the Jagiellonian University Museum with the beginning of the new academic year. Each month we will explain the Museum collection to you, choosing a single exhibit or a group of exhibits which usually are not shown to the open public. This month's feature are two cigars lit by Adam Mickiewicz and Antoni Edward Odyniec inside the Vesuvius crater.

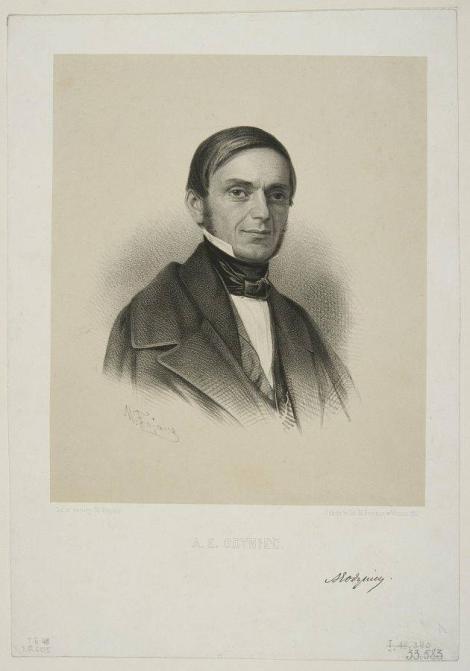

The collection of the Jagiellonian University Museum contains an interesting memento related to Adam Mickiewicz (1798-1855) and Antoni Edward Odyniec (1804-1885). It comes from an Italian trip these two poets and friends took in 1830. It also sheds light on the customs of the Romantic era. In those days, it was considered tasteful to collect all kinds of memorabilia, the more peculiar the better. The possession of such a collection influenced one's social standing and increased the social attractiveness of the collector. The cigars on display are an example of this kind of collecting from the Romantic era. In May 1830, Adam Mickiewicz, who loved hiking, arrived in Naples with Antoni Odyniec. They both had similar experiences, having been promoters of the Philomath Society’s ideas, but also co-prisoners in the trial of that society. They also travelled together through Germany, Switzerland and Italy.

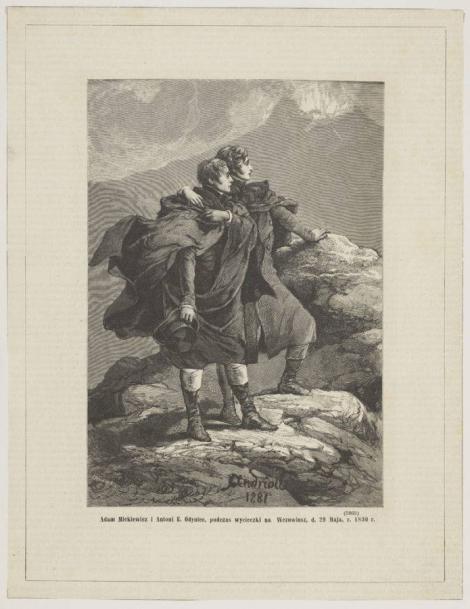

As was the custom at the time, the main highlight was climbing Vesuvius. What did one have to do on such an expedition? The traveller had to descend into the crater, light a cigar from the volcanic heat, collect chunks of lava, and cook an egg in the ashes. It is known that Mickiewicz and Odyniec did at least one of these things — they lit cigars in the crater of Vesuvius. Both described their impressions in letters, and so Odyniec wrote: We caught a glimpse of it [Vesuvius] from the top of one mountain [...] Adam took off by himself and made me take off my cap to admire it. [...] Having satisfied ourselves with the view of the outside and inside, we set off for the bottom of the crater [...] In one place alone we could see through the cleft a fire burning with a noise, strong and red as in a smelter, which reached all the way to the surface. After kneeling, we lit cigars in it, which I soon took from Adam to keep as a memento of my own. Mickiewicz, on the other hand, in a letter to his friend, the Philomath Franciszek Malewski, also included a description of the event, even though he was more laconic: I was in the crater of Vesuvius above its very mouth and looked into its throat, in its fire I lit my walking stick and cigar. In the third part of his drama Dziady, he referred to his volcanic observations when he wrote the well-known passage: Our nation like lava, / Outwardly cold and hard, dry and foul, / But the inner fire a hundred years will not cool / Let us spit on this crust and descend to the depths. Mickiewicz, who did not keep notes during his Italian journey, made an exception here, however, and wrote down an account of the expedition. He announced its creation in a letter to Zofia Ankwicz (mother of Henrietta Ewa Ankwicz): I will come up with a description of the crater, and, moreover, took the opportunity to send this text for publication in the St Petersburg Weekly. Unfortunately, the article did not appear, the correspondence with the Ankwicz family has not survived in its entirety, and the autograph of the “report” itself has been lost irretrievably. Vesuvius must have deeply stirred Mickiewicz's imagination, since he soon decided to travel alone to the area around Mount Etna in Sicily.

For romantics enduring the hardships of travelling, journey was a metaphor for life itself. As mentioned above, trips to Vesuvius and looking into the abyss of the crater so similar to vistas of hell were obligatory for Romantic poets visiting Naples. Even Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749–1832) could not resist the trend and climbed the volcano in 1782. This peak of hell which towers up in the middle of paradise — he emotionally described his impressions of the trip. The letters he sent to his friends had their edges charred by volcanic heat.

Naples and the Bay of Naples are among the places extensively described by researchers, writers, artists, and countless enthusiasts. Despite the rather arduous journey from Rome and the cost of travel, people came down to Naples often and willingly. Almost every Polish poet and writer who found themselves in Naples or the surrounding towns on the Bay and islands left some sort of trace in the form of poems or memoirs, letters, diary entries, and travelogues. It was a city striking in its otherness not only to visitors from faraway lands, but also to Italians themselves. Naples enjoyed a fame in Poland that became permanent during the Romantic era. The Italian saying vedi Napoli e poi muori (to see Naples and die), later popularised by Goethe, entered the dictionary of Polish proverbs and sentences probably around the middle of the 19th century. However, it must be remembered that the mythical image of Naples was created without a deeper knowledge of the customs and traditions of the place, often because of a complete misunderstanding of the geographical, social and political realities. Although Naples looked like a biblical paradise on earth in the eyes of a newcomer from the North, it hid many flaws, imperfections and dangers. The city witnessed natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, shifts in the tectonic plate, as well as epidemics of cholera, pestilence, and general extreme poverty that made it closer to a hell rather than an Eden. However, Naples was a picturesque and distinct city because of its inhabitants, their customs, philosophy of life, talents, qualities, and vices. All this fuelled the imagination of poets. In the vast literature on Italy, prose accounts and poetic works about Naples occupy an important place. All the most eminent Romantic poets visited Naples, and each of them left a trace of their stay there in the form of poetry and letters. For the Polish Romantics, pilgrims and exiles rather than ordinary travellers, visiting Naples and climbing to the crater of the menacing Vesuvius was a spiritual, metaphysical, and existential adventure. The ambition of the Polish wanderers was to gaze upon Vesuvius and think about the fate and spirit of their nation. Mickiewicz and Odyniec ascended Vesuvius on 1 June 1830, and exactly six years later, Juliusz Słowacki (1809–1849) stood on the same spot: I looked at Vesuvius until along the lava wall / The lumbering moon enters, on the crater it stands / And from there the white forehead turns to the world — he later wrote in the poem To Teofil Januszewski.

Much space was devoted to Naples by Antoni Edward Odyniec, who arrived in Naples with Mickiewicz on 8 May 1830 and left on 19 June of the same year. In Letters from a Journey, descriptions and impressions of his stay in Naples occupy as many as 89 pages. Odyniec was a very astute observer and a man who was familiar with literature and studies on Italy and Naples and its environs. He knew foreign languages and made direct use of foreign-language

texts. Unlike Mickiewicz, he was a persistent traveller and curious about everything, so he made the most of his stay of over a month, which was rather short, in Naples by visiting the city and both bays, that is the Gulf of Naples and the Golfo di Baia. Odyniec wrote that the author of Dziady became his guide and inspiration. Certainly, the bond between them was strengthened by the common experience of the Philomath Society during their youth, as well as the understanding that came from belonging to the same cultural tradition and place. Memories of the past and emotional ties to the Lithuanian landscape were a particularly important bond in their relationship. Odyniec echoed the beliefs and judgements already made about Mickiewicz on many occasions. He called him a “bard above bards”, a “prophet”, and a “genius”. In 1838, Zygmunt Krasiński admired Vesuvius, and in 1843, Cyprian Kamil Norwid and a group of friends went up to the volcano on horseback. The last great Polish Romantic often mentioned Vesuvius in his works.

In accordance with the will of Antoni Edward Odyniec, after his death in 1885 the case, together with the cigars lit in the Vesuvius crater by Mickiewicz and Odyniec, was donated to the collection of the Archaeological Cabinet of the Jagiellonian University (now the Jagiellonian University Museum).

Date of origin: before 1830

Length 3.6 cm (case); width 11.5 cm (case)

Inv. No. MUJ 6284; 3025/IV

Tobacco leaves, silk, cardboard, leather, lathed ivory

Donated by Antoni Edward Odyniec via Aleksandra Dunin-Borkowska, 1885

Photos:

Woodcut by Józef Holewiński based on a drawing by Michał Elwiro Andriolli titled Mickiewicz and Odyniec during a trip to Vesuvius. “Kłosów” Woodcut Manufacture, 1881, Warsaw. From the collection of the National Museum in Krakow, [kronika.gov.pl]

Antoni Edward Odyniec, Maksymilian Fajans (1827-1890), lithography. From the collection of the National Library of Poland [polona.pl]

mgr Maria Natalia Gajek, Dział Zbiorów Muzealnych