Exhibit of the Month is a series initiated by the Jagiellonian University Museum with the beginning of the new academic year. Each month we will explain the Museum collection to you, choosing a single exhibit or a group of exhibits which usually are not shown to the open public. This month's feature is the narwhal's tusk which excited human imagination for centuries, reminding them of the horn of a certain mythical creature: the unicorn.

A unicorn’s horn!

Too bad it’s only a narwhal’s tusk.

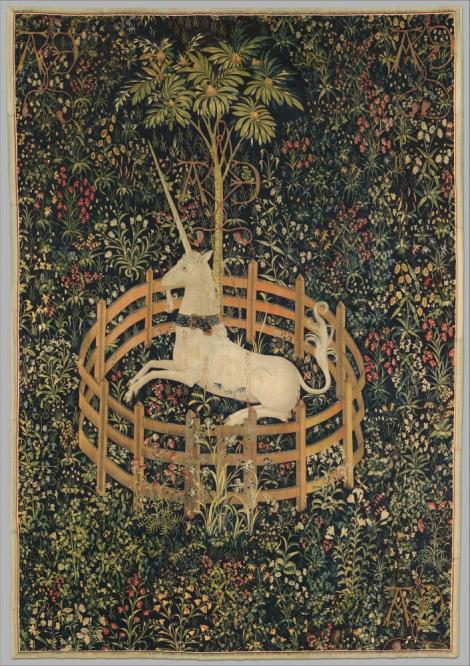

il. 1

Human beings weave tales in order to survive and understand the world. The myth of the unicorn, a magical animal with a single horn protruding from its forehead, has its origins in the Indus Valley during the third millennium before our era. Therefore, it is older than 5,000 years. The myth reached Europe by way of Mesopotamia, Iran, Byzantium, Ancient Greece and Rome.

Greek historian and the court physician of the Persian king Artaxerxes II, Ctesias of Cnidus, was the first person who described the unicorn in the 4th century BC. In his work On India (Indica) the author, who had never seen a unicorn, collected numerous accounts informing about the legendary creature. He wrote that this animal, native to India, resembled a horse or donkey and had a white body, purple head and dark blue eyes. The wild, elusive unicorn had a horn on its forehead that was one and a half ell long (between 0.660 and 0.787 metre), white at its base, black in the middle part and purple on its end. “It has been said that whoever drinks from that horn becomes resistant to incurable diseases because they never convulse, and they are immune to poison, and even if they have drunk a harmful liquid, they throw up and come back to health”.

Almost one hundred years later the unicorn was mentioned by the Septuaginta (mid-3th century BC – 2nd century BC), the oldest translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew and Aramaic into the Greek language. The Hebrew word רְאֵם [re׳em , wymawiane jako reh-ame׳] which appeared nine times in the original text referred to a wild ox that could be defeated only by God and was translated into Greek as monoceros (unicorn). This translation error contributed to the popularity of the unicorn myth in European culture. It was held for certain that the Biblical story confirms the existence of unicorns.

"The Physiologus", a Greek treatise on animals written by an anonymous author in the 4th century, also mentions the mythical animal. The work presents a compilation of numerous sources describing the unicorn, including the fragments of the Bible which referred to it. The treatise became a source of inspiration for the authors of all European bestiaries. Chapter sixteen, On the Unicorn and How To Catch it, contains the following sentence: “This animal is called monoceros in Greek and unicornis in Latin”. Similarly to the Indian unicorn, it would only allow an innocent maiden to catch it.

During the 11th and 12th century, "The Physiologus" was translated into vernacular languages. The unicorn began to symbolise Christ and his human nature while its horn was associated with the horizontal arm of the cross, as well as with the unity of God Father and Christ. The naturally spiral form of the horn increased the perception of its sanctity. The columns in Solomon’s temple were also spiral. Similarly, the head of the bishop’s crosier is also coiled into a spiral. The figure of the unicorn, its history and scenes depicting a unicorn hunt appeared in poetry, works of theology, but also in works of sacral and courtly art. The popularity of unicorns reached its peak in the 14th and 15th century. The mythical animal appeared almost everywhere, including painting, sculpture, graphic arts and ornamental art (pic. 2). Some preserved aquamaniles, elaborate water vessels, were made in the shape of a unicorn (pic. 3). Already in the 13th century the unicorn became a symbol of virtue, chastity, faithfulness, and courage (pic. 4). The animal also appeared in heraldry (pic. 5). King James I incorporated the white unicorn from the Scottish coat of arms into the arms of the United Kingdom. A similar example in Polish heraldry was the Bończa coat of arms (pic. 6). Eventually, depictions of scenes from the story of the unicorn were met with criticism. In 1563, the Council of Trent banned depictions of the Annunciation combined with a unicorn hunt (pic. 7) as being contrary to the teachings of the Church. Royal, ducal and ecclesiastical inventories from the 12th to 16th centuries mention unicorn horns. They often found their way into royal treasuries as diplomatic gifts given to monarchs (such as the unicorn horn given by King Sigismund Augustus to Emperor Ferdinand I).

Unicorn horns were used from the 12th to the 16th century to make crosiers, shafts of processional candlesticks or even the shafts of royal or even cardinal sceptres (e.g. the cardinal sceptre in the Treasury of the Jagiellonian University Museum which originally belonged to the Bishop and Cardinal Bernard Maciejowski of Cracow, who died in 1608). They always were objects of great symbolic value which were used during exceptional court or church ceremonies. Placed near the main altar like relics, they could be seen and adored by the faithful. Priceless drinking cups were made from ”unicorn horns”, elaborately framed by goldsmiths. No jewellery or common objects were made from the “unicorn horn”, as this would have been a kind of insult to its value. This attitude changed when the unicorn horn became a mere narwhal tusk in the popular consciousness. In effect, it then ended up in cabinets of curiosities as just another object belonging to a collection of exotic natural specimens. Eventually, it simply became a natural material from which a walking stick or a billiard cue could be made.

Narwhal

During the Oligocene epoch (33.7 – 23.8 million years ago), the first toothed whales appeared, a group that included narwhals. This species developed about half a million years ago, inhabiting the area of the Arctic Ocean, the youngest ocean on Earth.

Around 5,000 years ago, the Inuit people arrived in Greenland from Northern Siberia. They hunted polar bears, walruses and narwhals. The latter would come so close to the coast of the island during the mating season in summer and only then, for a short time, the hunters were able to kill them. Both bears and narwhals were surrounded by reverence. The native Greenlanders attributed magical significance to them. They made harpoons out of narwhal tusks, just as they do today. We know that the Inuit independently invented the screw. Did they not copy the spirally twisted tusk of the narwhal?

From around 985 to 1400, there was a Viking colony in Greenland. During that period the trade began in polar bear skins and also narwhal tusks which were bought by merchants from the Netherlands and Denmark.

The name narwhal used today comes from the Proto-Norse language used in Scandinavia until 1390 and also spoken by the Vikings (nār meaning carcass, a reference to the colour of the animal, and hvair meaning whale).

The diocese of Trondheim was the centre mediating the trade between Iceland and Norway. It was the capital of Viking Norway until 1217 and the capital of the archdiocese from 1152 to 1532. The fang of the narwhal was perfectly suited to play the role of the “unicorn horn”. It was an answer to the desire to find material proof of the existence of unicorns. The narwhal itself, however, did not suit that image. The somewhat comical appearance of a plump animal with a gigantic spike in its head doomed its chances of playing the role of epic hero. In the 16th century, a narwhal fang ("unicorn horn") three metres long and weighing 10 kilograms had a value of 200 kilograms of gold, equivalent to 10 million euros today. Queen Elizabeth I of England bought the “unicorn horn” for 10,000 pounds, a price equivalent to the value of an entire castle. Not surprisingly, the Scandinavian merchants did not care to inform subsequent buyers that the horn being sold was not a “unicorn horn”, but a narwhal tooth. A strange forgery on a European scale took place. The “horn” itself was an original part of an animal. The information about what kind of animal it was and where it came from was an element of deliberate misrepresentation. The falsification stopped when the results of the voyages to Greenland and the study of the Arctic fauna were published. Prior to this, the narwhal almost never appeared in mediaeval sources, with a few exceptions. In the work of Albert the Great, a Dominican friar and German philosopher, De animalibus, written in the 13th century (published in print in 1478), the narwhal was described as a "sea fish having one horn on its forehead". In the mid-13th century, the Speculum Regale mentioned that the narwhal was inedible, smaller than most cetaceans, it avoided fishermen, its fang was straight and smooth, as if shaped by hand tools. In both of these works there is no mention of the narwhal having a spirally twisted fang. However, they did not influence the popularity of the unicorn myth. The Speculum and other works classified the narwhal as a cetacean, and therefore a marine fish. In later compendia of aquatic fauna, it became known as the "unicorn fish".

In 1638, Ole Worm (1588–1655), a Danish physician and natural scientist, put an end to the recognition of the narwhal tusk as the horn of the unicorn, but did not doubt its healing properties.

In 1645, Thomas Bartholin (1616–1680), an apprentice of Worm, Danish physician, anatomist, mathematician and theologian, published the work De Unicornu observationes novae (...) in Padua, in which he reported on 50 specimens of narwhal tusks known to him and included a drawing of a narwhal skull with a single tusk.

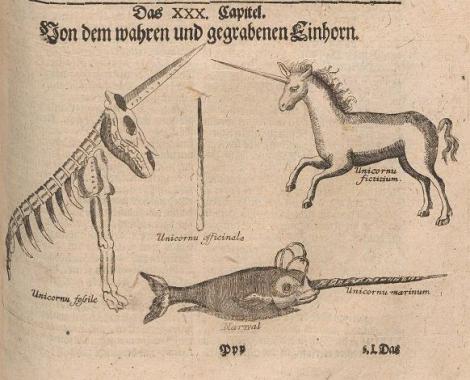

In 1704, the work Museum Museorum (...) was published, written by Michael Bernhard Valentini, collector of curiosities, the personal physician to Margrave of Hessen anda professor of experimental sciences and medicine at Giessen. In chapter XIII of "Von dem wahren und gegrabenen Einhorn" [On real and fossil unicorns], the author included a drawing depicting a narwhal (Unicornu marinum), a unicorn fossil (Unicornu fossile), a fictitious unicorn (Unicornu fictitum), and the fang of a medicinal unicorn (Unicornu officinale) (pic. 8).

In 1751, Denis Diderot's French encyclopaedia included an entry on the licorne (unicorn) which mentions that what was thought to be the horn of a fantastic unicorn was the tooth of a fish, a cetacean called narwhal.

Beata Frontczak

The exhibit will be displayed in the main exhibition from 9 March!

Selected bibliography:

J.W. Einhorn. Spiritalis unicornis. Ein Einhorn als Bedeutungsträger in Literatur und Kunst des Mittelalters. München, 1998 (available online: https://digi20.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/bsb00050106_00001.html)

A. Pluskowski. Narwhals or unicorns? Exotic Animals as Material Culture in Medieval Europe, “European Journal of Archaeology”.Vol. 7, 204. 291–313.

Online sources:

https://www.nationalgeographic.de/geschichte-und-kultur/2021/01/narwale-und-einhoerner-verbindet-eine-lukrative-geschichte

https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/content/journal/entdecken/das-einhorn-von-magischen-missverstaendnissen-jungfrauen-und-jesus-christus

http://covenantarthistory.blogspot.com/2015/12/myth-to-religion-and-back-unicorns.html

https://naukawpolsce.pl/aktualnosci/news%2C27590%2Clekliwe-serce-narwala.html

https://www.wilanow-palac.pl/kiel_narwala_czyli_rog_jednorozca.html

https://polona.pl/item/iednorozec-zacny-y-starodawny-zacnego-y-starodawnego-w-polscze-domv-ich-mosciow-pp,OTE2Njc0MDE/7/#info:metadata

http://www.muzeum-przyrodnicze.uni.wroc.pl/index.php?go=ciekawe-eksponaty-narwal-jednozebny

https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narwal_jednoz%C4%99bny

https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/R%C3%B3g_jednoro%C5%BCca

https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jednoro%C5%BCec

In the Museum's collection

-

Narwhal tusk converted into a pool cue. Turned, polished, decorated with marquetry made of various wood types and mother-of-pearl panels. France, first half of the 19th century. Probably from the collection of Duke Franciszek Ksawery Drucki-Lubecki, Minister of the Treasury of the Kingdom of Poland in the government of Tsar Nicholas I, then property of Zygmunt Pusłowski, his grandson. Length: 134.7 cm.

Narwhal fang. -

Gift of Eufemia Rogawska, widow of Karol Rogawski (d. 1889), the latter a great donor to the Jagiellonian University who bequeathed nearly one hundred works from his collection to the university in 1881. Length: 183.5 cm. Inv. no. MUJ–85–V.

-

Narwhal fang used as a walking stick, with brass spike and the knob made of turned horn. Setting: France, first half of the 19th century. Gift of Irena Rylska, 1880s. Length: 90 cm. Inv. no. MUJ–84–V.